Now well over 2000 miles since Ipswich, we have seen some crazy stuff: weather, places, people, etc. But something has surprised me… I don’t take THAT many photos.

Don’t get me wrong, I carry a camera of some sort everywhere and I’m taking a lot of photos – even if it is just for a tweet or Instagram. But hours and hours and hours at sea… is there really nothing to photograph out there?

Before our first “out of sight of land” experience crossing the Thames from the River Orwell to Ramsgate back in December, I had been offshore plenty of times. Most people who travel have, for that matter. Ferries – like the ones I’ve taken from Patmos, Greece, to Bari, Italy; or the one from Hollyhead over to Dublin – certainly go “offshore” and they are far out of the sight of land. And most cruise ships (of which I have done one) hug the coast, but there are times that they pass outside of sight of land.

But these big-boat offshore experiences did not prepare me.

What is out there? A whole lot of nothing. In every direction. And, quite often, it isn’t long that you’re out of sight of land that you’re also out of VHF range, too. Only the scratchy high-power bursts from the area coast guard can be heard. Then, after a little while longer, the only thing you’re able to hear is the occasional chatter from fishing boats that might be just at the horizon. And by “occasional chatter” I mean little transmissions of what sounds like gruff mumbling occasionally laced with punctuations of profanity, often the only words that are actually comprehensible.

But, basically, it is incredible how much nothing there is out there.

Perhaps an example might be in order?

On any given hour offshore, I could sit on the side of the cockpit.

The water directly beside the boat is approximately a four foot drop, but beneath that is anywhere from a few dozen to a few thousand meters of water.

To my right…

…and to my left…

…the boat is its own little kingdom. This is all there is. And, if you look really close at the photo of the “to my right” photo above, you’ll actually see the faint darkness in the haze of Cabo Finisterre, the northwest tip of Spain.

But even at a dozen miles offshore, everything is extremely far away. And a “close pass” could be by a mile or more. The AIS warns us of targets within a half-mile radius. But more on that in a moment…

Most of the time, this is what it looks like:

A wide angle shot straight out. Vast openness of sky and sea, water in every direction. The next thing in that direction is the North American continent.

A wide angle shot straight out. Vast openness of sky and sea, water in every direction. The next thing in that direction is the North American continent.

Believe it or not, though, there are actually FIVE fishing vessels “close” in the above photo. Here are three:

Compare the two? See them!? Yeah… it takes a lot of effort out there, too. And, to help you a bit, here is the zoomed in version, overlayed with the wide angle version:

Compare the two? See them!? Yeah… it takes a lot of effort out there, too. And, to help you a bit, here is the zoomed in version, overlayed with the wide angle version:

On the map, these boats are within a few miles: I don’t remember exactly, but I’d guess within two or three miles. And these aren’t small boats. They’re, on average, about twice the length of Proteus. The big commercial fishing boats like these weigh in around 80 feet.

On the map, these boats are within a few miles: I don’t remember exactly, but I’d guess within two or three miles. And these aren’t small boats. They’re, on average, about twice the length of Proteus. The big commercial fishing boats like these weigh in around 80 feet.

Now… just for kicks and giggles, what does a sphincter-puckering close pass look like? This is about a quarter mile pass. (And he’s in the 600 foot range.)

Still not that close, right? Well… you only think “a quarter mile isn’t that close” until it happens in the middle of the night.

But most of the time, it looks like this…

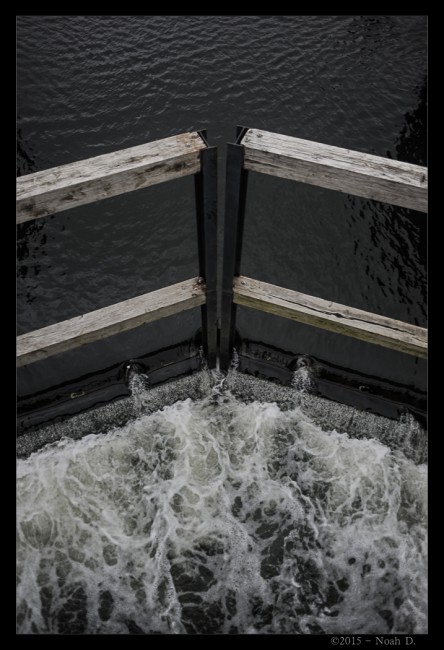

…and seeing something as innocuous as foam on the water dozens or hundreds of miles out at sea with absolutely nothing around makes the mind wander: “Maybe there’s a submarine under us!?” “Maybe the Cracken is coming!?” “Maybe there’s a whale!?”

It is probably just the foam from a boat that passed hours ago.

It is probably just the foam from a boat that passed hours ago.

As the quote says on our homepage, the sea is an amazing liberation from human scale. Compared to the sea, we are always children standing on the beach thinking we can see miles and miles and miles and maybe if you squint a little I bet you could just make out the other side… but, in reality, you’re not even able to get to double digit miles.

Can you understand my difficulty in making photographs on passage? There’s so much out there, how can I even make a photo of it: the vast emptiness that covers most of the world is not able to be captured in an image. And perhaps the handicap is made worse because we make cameras to take photos at the perspective of humans. (That’s why people naturally think wide angle photos are naturally “more interesting”: we normally don’t see that way.) So, to capture anything on the ocean is naturally limited to our inability to wrap our minds around incredible immensitudes.

To comprehend the sea, then, I suppose we have to get outside ourselves, outside the limits of human scale, and look at “close” on the scale of “multiple miles.” Then, almost everything visible is close. Perhaps things just beyond the horizon is still pretty close! And, at that scale, when does “far” begin?

I wonder if this is the secret that needs to be unlocked in order to finally get some peace in this world. When everything is close and nothing is really that far, “us” and “them” starts to get really silly, really small-minded.

I prefer to be big-minded. I prefer to be at the scale of the sea.